Innovation in Education

The Joint Force has a deep appreciation for the importance of communication systems—across commands and between people. Leaders, civilians and servicemembers, officers and enlisted, often forget that communication and the ability to communicate is deeply generational. Dr. Fred Kienle developed the content of this article and oft presented it to new faculty at the Joint Forces Staff College. Campaigning asked Dr. Kienle to convert his slides to an article to enable broader sharing and consideration, since communication is a key enabler for so much of what the Joint Force strives for.

Someone posted a motivational sign on the wall of a Joint Professional Military Education (JPME) college recently. The sign proclaimed, “the mind is like a car battery, it recharges by running.” Attributed to Bill Watterson, the inspirational, if not brainy quote, made perfect sense to the administrator or faculty member who placed the sign in the busy hallway.1 But to someone growing up in a generation with an increasing number of electric vehicles, the quote might seem ridiculous. Most any teen in Generation Z can confidently argue that electric vehicles can’t charge their own batteries; batteries need to be plugged into a power source for recharging. Maybe brainy and maybe motivational, but the quote is certainly a generational anachronism. Intending to create unity, it serves to illustrate the risk of ignoring the existing differences between the generational cultures that populate the JPME enterprise. Today’s JPME faculty and students generally find themselves as products of at least two different generational cultures, with slightly different thoughts, ideas, and educational preferences, which can, if neglected or poorly addressed, diminish learning and create contentious classroom dynamics.

The U.S. Joint Professional Military Education (JPME) enterprise is clearly in the business of amalgamating cultures through a process termed “acculturation.” Acculturation can be defined as “a change in behaviors and thinking among a group of individuals as a result of continuous contact.”2 The CJCSI 1800.01F Military Education Policy charges all of U.S. Military’s JPME I & II accredited military colleges to achieve acculturation through “a mix of students and faculty to foster a joint learning experience” and through the creation of “common beliefs and trust that occurs when diverse groups come into continuous direct contact.”3 JPME institutions have a mission to mitigate, if not overcome, the profound differences in culture, attitudes, underlying values, traits, and worldviews of the Services.

Defining Generations and Culture

Service cultures are not the only cultures clashing in JPME classrooms. Military and Service cultures are a complex product of national values, history, experiences, social necessity, technologies, amongst other considerations. Service cultures are demonstrated through multiple artifacts, espoused values, and basic assumptions.4 Each of the six military branches has its own set of terms and acronyms that relate to traditions, roles, missions, job titles, tactics, and expectations of military service members and their organizations.5 Each military branch also has its own set of moral codes such as duty, honor, courage and strength, which shape service-members’ personal and professional outlooks.6 The immutable existence of cultural differences between Services is well recognized. JPME institutions acknowledge and address different Service cultures but often make far less effort to recognize and address generational differences existing across their respective populations. The multiple generational cultures might be as different as the ever-present Service cultures in JPME classrooms.

A generation is often defined as a group of people born within a twenty-year time period and during the same general era in history.7 A generation usually embraces the aggregate of all people born over the length of one distinct phase of life: childhood, young adulthood, midlife, and old age. Generations are identified, from first birthyear to last year, by looking for cohort groups of the twenty-year duration that share three criteria: first, members share what many researchers term "age location in history”; generations tend to encounter key historical events and social trends at about the same phase of life; and those in a generational cohort generally share common beliefs and behaviors. Using that definition as a frame of reference, members of a generation are shaped in lasting ways by the specific and similar eras they encounter as children and young adults. Aware of the experiences and traits that they share with their peers, members of a defined generation cohort also share a sense of common perceived membership in that generation.8 Like Service cultures, generational cultures are a complex product of multiple distinct factors that impact personal values, assumptions, behaviors, and behaviors. Acknowledging and understanding the generational cultures is important for JPME institutions.

Generational culture develops as a result of multiple environmental events. Events of late childhood and adolescence, coupled with distinct parenting strategies and contemporary technological advances merge to set the life course for each specific generation type.9 Each generational cohort forms its quasi-unique persona based on the social conditions cohort members were exposed to at the most formative period of their lives, childhood and adolescence. Significant events are seared into young memories and shape understanding and attitudes. When the events of Kennedy’s assassination, the Challenger Disaster, and 9/11 occurred, each age group, whether child, teen, middle-aged parent, or senior grandparent, observed and processed the events according to their developmental status. The similar processing according to developmental status creates shared social influences, successes, tragedies, and technologies during formative years that substantially contribute to a shared societal personality and world view. Parenting styles and tendencies also have indelible influence on a generational cohort’s maturity, independence, and decision-making skills. A cohort’s general receptivity, dependence, and attitudes toward emergent technology are shaped while young, both within the home and at school. Yet another impact defining each generation is that generational cohort’s reaction to its predecessors, usually including parents, teachers, and other influencers. The breadth of the changing environment and events that unfold in a cohort’s most formative years helps define that cohort’s generational attributes.

Parenting methods and styles, driven by social and technological changes, shaped how children from each generation viewed and experienced the world.10 The Greatest Generation, having survived World War II, focused on raising their families and valued hard work. They knew about loss and hard times, and their realistic and pragmatic way of living greatly influenced their parenting style, which emphasized the virtues of labor and effort. The Silent Generation married young and raised children young; they also popularized divorce and raised their children to be seen and not heard. Baby Boomers, born in the prosperous shadows of post-World War II are the parents of late Gen Xers and today’s Millennials. They raised their children with an focus on increasing their children’s quality of life, preparing them for college, and worrying about how their children felt about growing up. Baby Boomers were markedly different parents from the two preceding generations. Generation X parents focused on work-life balance, dedicating study and time to the role of parenting while supporting their children’s broad development and choices for a variety of individual lifestyles. Socially open-minded Millennials are marrying less and having less children, engaging in a parenting style markedly different from derisively termed “helicopter parenting” that characterized the approach of their parents. The differences in parenting styles between successive generations greatly impacts generational values and societal views with regard to family, authority, work ethic, entitlements, expectations, and commitment.11 Differing generational approaches to parenting shape how each successive generation cohort approaches nearly every facet of their lives.

Just as technology—television, travel, communications, and media—influenced parenting styles, and it also directly influenced learning styles. Differences in access to and familiarity with technology is one of the major differences between generation cohorts. Generation Z has been born into the digital; millennials are digital natives; generation x’ers are early tech adopters; baby boomers are digital immigrants who are generally less tech-savvy or tech-reliant. Younger generations are generally more prone than their older counterparts to embrace new technologies, and the younger generations are also more likely to place value and trust in emergent technological capabilities.12 Younger generations tend to be more technology-based, exhibit innate abilities to quickly find information, and have broad access to updates across the global socio-political environment.13 While technology always influenced human life, it now exerts more power and influence than in preceding generations. Technology is the personal portal for communication, learning, news feeds, updates, images, entertainment, music, and daily schedule.14 Degrees of technology acceptance and application impact almost every aspect of modern life, defining a key part of a generation.

The major events of late childhood and adolescence coupled with distinct parenting strategies and new technologies set a life course for each specific generational cohort.15 The realization that life experiences shape the beliefs, values systems, attitudes, skills, and behaviors of specific age cohorts is essential to understanding how different generational cohorts of student officers think.16 Culture constantly evolves, and successive generations embrace a particular perspective within the broader culture. In embracing a perspective, the opportunity for clashes and misunderstandings between generations increases. Teaching becomes increasingly problematic as conflicts generated by cultural difference arise in the classroom because the generation and sharing of knowledge diminishes. The effectiveness of JPME curriculum delivery and andragogical approaches become suspect if faculty praxis fails to acknowledge and account for the existence of cultural diversity in the classroom.

JPME Generations and Demographics

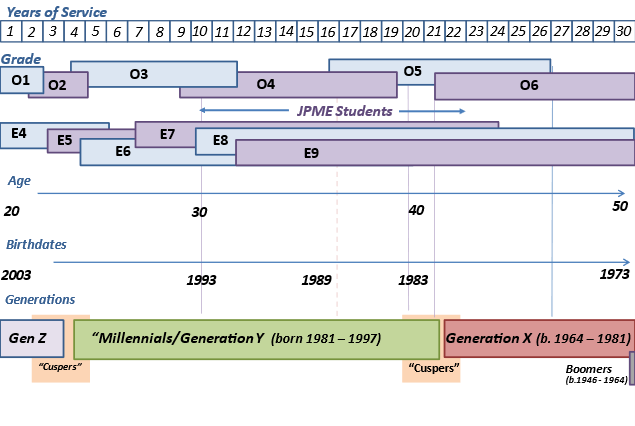

The JPME enterprise accounts for members of three distinct generational cohorts as defined by the Pew Research Center. Most military PME institutions include leaders and senior administrators born between 1945 and 1964, the last of the baby boomers. JPME faculty, generally in the grades of O-5 to O-6, reside squarely within the confines of generation x, born between 1964-1981. JPME students, principally junior O-4s to very junior O-6s, are considered the millennials, born between 1981 to almost 1997, and the last of the generation x’ers are progressing through the senior level education institutions.17 The distinctive grouping should come as no surprise, as generational differences are prevalent in the military due in large part to the military’s hierarchical structure with officer promotions based predominantly on performance at successive grades and time in service.18 Military leadership, faculty, and student bodies also have many cuspers amidst their ranks. Cuspers are those born within 3-5 years of a generational divide that favor and display characteristics from both relative generations.19 Cuspers tend to be concentrating in two distinct generations over the remainder of this decade.20 More and more, JPME students tend to be millennials amongst a faculty predominantly comprised of the generation x cohort. The requirement for cross-generational understanding in JPME institutions is fundamental to mission accomplishment.

The baby boomer generation includes those who served in the military during the Cold War and Desert Storm, inheriting a strong work ethic from their parents and learning in traditional linear classrooms. As a result of their early life experiences, boomers live to work, tolerate digital technologies, and are generally optimistic. Many boomers tolerate rather than embrace popular social media technologies, are warming to classroom technologies, and retain very traditional views of academia. While baby boomers are leaving the JPME enterprise, their presence remains across the political landscape and among the most senior military leadership. Baby boomer influence will likely remain for some time.

Figure 1: JPME Students Across the Generations 2023.

The majority of JPME leaders, and nearly all JPME faculty, are generation x. Generation x includes most senior officers across the Services. Some generation x military officers served in Desert Storm, but most had their formative military experience in Bosnia, Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF). Generation x leaders and faculty were raised as latchkey kids because both parental figures worked and increased divorce rates, which lead to the rise of one parent families. Generation x proved more independent than their parents, and lacked the optimism of their parents due to experiencing memorable economic crises, failed political leaders, and the Challenger Disaster that demonstrated the fallibility of technology. Generation x observed a change between employers and employees due to downsizing, furloughs and layoffs that suggested a shift in commitment. The end of the Cold War led to similar reductions in force across the military. Most of generation x did not share their parent’s “live to work” ethic and, at least initially, saw the military as a job and not a committed lifestyle.21 Generation x learned to adopt and adapt to new technologies, experienced some of their early learning in semi-formal environments, such as pods and work groups, and recoiled against educational requirements they deemed irrelevant or not valuable.22 As generation x assume senior leadership roles, they may occasionally struggle in their efforts to truly connect to millennial junior grade officers.23 Millennials often view generation x as overly traditional, often inflexible, and risk averse, but they also see generation x as loyal, independent, and resilient.24

According to most sociologists, millennials are sociable, optimistic, talented, well-educated, collaborative, open-minded, influential, and achievement oriented. Their formative years of parental and societal focus on children and family, and busy, nontraditional, yet highly structured adolescent lives influenced their prevailing attitudes. Many researchers believe that society’s child-focused parenting of the 1980s and 1990s contributed to the characteristics of entitlement and specialness frequently cited as detrimental but prevalent millennial traits.25 Based partly on their early educational environment, millennials exhibit a definite inclination to work in teams. They make decisions as a team and frequently measure themselves against their peers as a result of social media habits. The team-oriented lifestyle and social media habits of millennials might also explain why their engagement in political and civic activities may surpass the young people of previous generations.26 Millennials were raised with frequent positive reinforcement from multiple sources, such as social media likes, savor multi-sensory stimulation, and expect a synthesis of learning and entertainment—edutainment.27 Millennials learn differently from their predecessors that drive preferences and expectations when they are students. Millennials have critical perception of generation, which should consider JPME faculty since the majority of current JPME students are and will be millennials over the next decade.

Boomers and generation x will benefit from understanding, managing, and adapting to millennial preferences and expectations. Understanding will allow leaders and faculty to home in on and resolve the seemingly contradictory tension between millennial preferences. Most millennial students subscribe to similar learning preferences in their contemporary learning environment. Based on the life experiences that create preferences, millennials expect JPME curriculum to incorporate teamwork and group efforts in problem-solving exercises. Millennials tend to crave active and interactive direction, and they tend to expect their faculty to know more than they do. Because of their rearing, millennials expect constant attention from faculty accompanied by frequent and detailed feedback, particularly positive feedback. Previously accustomed to regimented childhood schedules, millennials desire a delicate balance between classroom supervision and an organized, flexible learning environment. Millennial students enjoy challenging faculty assertions, and they are quick to search for contrarian assertions on the internet. Some of the challenges millennials present are grounded in feelings rather than facts. They expect skills and information that will make life less stressful and ensure professional success, based on the belief that there is a clear right-way that can be explained. Most millennial students are prolific readers and desire more supporting information from more sources while expecting concise and to the point readings.28 Products of their formative years, most millennials exhibit clear preferences is learning styles, classroom management, and curriculum design that necessitate consideration from leadership and faculty if they hope to have a positive effect on millennial JPME students.

Iraq and Afghanistan, the formative conflicts of millennial’s careers, led to the development of a unique professional ethos. In a world of social media, instant reporting, and internet virality, millennials became comfortable with attention and the volatility of public opinion, and considered in conjunction with the interactivity of the internet, suggests a comfortability with institutional change and the expectation that their needs and desires will be accommodated. Millennials are products of their environment, experience, and education. It is disingenuous, if not foolish, to expect millennial JPME students to adapt to educational processes and practices that were developed for the culture of a different generation. Accommodations and innovation are requisite to ensuring cross-generational acculturation throughout JPME.

While JPME educational processes must consider and accommodate the culture of the millennial generation, this should not be a dramatic overhaul or abandonment of what is currently working. The traits, values, and ethos of millennials are broadly indicative of the generational culture but are probably not uniformly embodied across the JPME student population. Many factors separate individuals beyond when they were born, and military members of a generation have certainly experienced starkly unique occurrences that shaped individual preferences, strengths, and weaknesses. The dates that separate generations are somewhat contrived, and it is sometimes difficult to categorize those whose age puts them at the cusp of those dividing lines. Generation cohorts certainly consist of diverse people and groups of people from all walks of life. And many ostensible generational characteristics are likely life-stage effects, which are found every generation as the cohort generally moves from less responsibility in young adulthood to more responsibility in later years. Yet, as argued by many respected research organizations, age is definitely one of the most important predictors of each individuals’ values, attitudes, and behaviors. Where military officers fall in their career, their life cycle, global events that occur during their lives, and the influence of their peers shape the traits of their entire generation.29 Understanding the realities and differences of generational cultures is essential to managing the interaction of multiple cultures in the JPME academic setting.

Bridging the Gap

The proverbial generation gap is real, but it can be bridged. JPME institutions will serve themselves well if they educate leaders and teachers on recognizing generational differences and cultural preferences. Leaders and faculty should routinely encourage cross generational interaction to include mentoring, sharing experiences, and solicitation of fresh perspectives. JPME’s Outcome Based Military Education (OBME) suits millennials’ preference for a focus on results rather than process and enables a broad range of learning and communication styles. Team-based problem-solving exercises also suit millennial learning preferences and lend themselves to integration of technology and media enhancements favored by millennial learners. Exercises support more frequent feedback, additional learner responsibility, and opportunities to customize learning to satisfy millennial student preferences. Finally, offering millennials a voice in their classroom governance and a degree of open classroom organizational structure tends to gain more collective buy-in. Understanding the culture of the millennial generation facilitates targeted JPME instructional design and more favorable outcomes.30

Generational cohort differences can be as significant as the differences between the Services or the other cultures routinely found across the gamut of JPME classrooms. As the JPME enterprise advances, consideration of the differences between the three or four generations involved in JMPE is critical. While JPME institutions have long focused on acculturation between the Services, understanding between governmental organizations, and recognition of different national differences, they may not have truly analyzed the impact of competing generational cultures. As members of the millennial generation dominate the JPME student population, generation x and remaining boomer faculty and leaders must acknowledge and master and lead acculturation between multiple generations.

The environment facilitating acculturation should extend well beyond simply acknowledging, understanding, and bridging Service differences; it also necessarily includes bridging the cultural differences between civilians, foreigners, government agencies, academic institutions, and generations. Yes, differences in values, worldview and culture between generations within and across each of the services may be as profound as those differences between the Services themselves.31 The distinct generational differences that exist in JPME classrooms have been clearly identified by psychologists, sociologists, and everyday managers. The generational differences manifest themselves in the way military officers at various ranks and grades approach duty, work-life balance, loyalty, trust, authority, ethics, commitment, technology, and a wide range of other important issues related to the JPME enterprise.32 Generational differences can be as significant as the differences between the Services or the other cultures routinely found in the gamut of JPME classrooms.

Dr. Fred Kienle, COL, USA (Ret) was a professor at the Joint Forces Staff College of the National Defense University. He was the first director of the Joint Advanced Warfighting School, served on dozens of JPME accreditation teams, and continues to support military and government educational activities.

2. U.S. Department of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction 1800.01F, Officer Professional Military Education Policy (OPMEP), Joint Chiefs of Staff, (Washington, D.C., 2020), https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/education/cjcsi_1800_01f.pdf?ver=2020-05-15-102430-580

3. U.S. Department of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Manual 1800.01, Officer Professional Military Education Policy (OPMEP), CJCSM 1800.01, Joint Chiefs of Staff, (Washington, D.C., 2022), https://www.jcs.mil/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=EuuLOOliw14%3d&tabid=19768&portalid=36&mid=48785.

4. Edgar Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership, Jossey Bass, (San Francisco, CA, 2010).

6. C. A. Kuehner, “My Military: A Navy Nurse Practitioner’s Perspective on Military Culture and Joining Forces for Veteran Health”, Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, (Vol. 25, 2013), 77–83; C.D. Luby, “Promoting Military Cultural Awareness in an Off-Post Community of Behavioral Health and Social Support Service Provider, Advances in Social Work, (Vol. 13, 2012), 67–82.

7. Graeme Codrington and Susan Grant-Marshall, Mind the Gap!, Penguin Books, (Johannesburg, South Africa: 2004), 12-13 and 104-117.

8. William Strauss and Neil Howe, Generations: The History of Americas Future, William Morrow (New York, N.Y., 1991); William Strauss and Neil Howe, Millennials Rising, Vintage Books (New York, NY, 2000).

9. William Strauss and Neil Howe, Generations: The History of Americas Future, William Morrow (New York, N.Y., 1991).

10. Charise Rohm Nulsen, “A Look at the Different Generations and How They Parent,” Family Education, Accessed on December 1, 2022, https://www.familyeducation.com/family-life/relationships/history-genealogy/a-look-at-the-different-generations-and-how-they-parent.

11. Rika Swanzen, “Facing the Generation Chasm: The Parenting and Teaching of Generations Y and Z”, International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, (Vol. 9, 2018), 125-150, Accessed on November 30, 2022, https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs92201818216.

12. K. Carbary, E. Fredericks, B. Mishra, and J. Mishra, ”Generation Gaps: Changes in the Workplace due to Differing Generational Values”, Advances in Management, (Vol. 9, 5, May 2016) 1-8.

13. Scotty Autin, “From the Lost Generation to the iGeneration. An Overview of the Army Officers Generational Divide”, From The Green Notebook, 2020, Accessed on December 8, 2022, https://fromthegreennotebook.com/2020/01/07/from-the-lost-generation-to-the-igeneration-an-overview-of-the-army-officers-generational-divides/.

15. William Strauss and Neil Howe, Generations: The History of Americas Future, William Morrow (New York, N.Y., 1991).

16. Michael Coomes and Robert DeBard, “A Generational Approach to Understanding Students”, New Directions for Student Services, (No. 106, 2004), 5-16.

18. Leonard Wong, Generations Apart: Xers and Boomers in the Officer Corps, Strategic Studies Institute, (Carlisle, PA., 2000), https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA385404.pdf.

19. L.C. Lancaster and D. Stillman, When Generations Collide Who They Are. Why They Clash. How to Solve the Generational Puzzle at Work, Harper Business, (New York, N.Y., 2003).

20. L.C. Lancaster and D. Stillman, When Generations Collide Who They Are. Why They Clash. How to Solve the Generational Puzzle at Work, Harper Business, (New York, N.Y., 2003).

21. Leonard Wong, Generations Apart: Xers and Boomers in the Officer Corps, Strategic Studies Institute, (Carlisle, PA., 2000), https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA385404.pdf.

22. Thomas Reeves, Do Generational Differences Matter in Instructional Design?, University of Georgia, Accessed on December 2, 2022, https://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/imported-files/10c-Gen-Diff-Matter.pdf.

23. Scotty Autin, From the Lost Generation to the iGeneration. An Overview of the Army Officers Generational Divide, From The Green Notebook, 2020, Accessed on December 8, 2022 https://fromthegreennotebook.com/2020/01/07/from-the-lost-generation-to-the-igeneration-an-overview-of-the-army-officers-generational-divides/.

24. Al Boyer and Cole Liveieratos, “Changing Character of Followers: Generational Dynamics”, Modern War Institute, June 16, 2022, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/the-changing-character-of-followers-generational-dynamics-technology-and-the-future-of-army-leadership/.

25. C. Raines, Connecting Generations: The Sourcebook for a New Workplace, Crisp Publications, (Menlo Park, CA, 2003), 11.

26. H.M. Lopez, P. Levine, D. Both, A. Kiesa, E. Kirby, and K. Marcelo, The 2006 Civic and Political Health of the Nation: A Detailed Look at How Youth Participate in Politics and Communities, Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (October 3, 2006), https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/reports/youth_voting/circlereport100306pdf.pdf.

27. William Strauss and Neil Howe, Millennials Go to College, Lifecourse Associates, (Great Falls, VA,2007), https://archive.org/details/millennialsgotoc0000howe/page/n3/mode/2up.

28. L.C. Lancaster and D. Stillman, When Generations Collide Who They Are. Why They Clash. How to Solve the Generational Puzzle at Work, Harper Business, (New York, N.Y. 2003); B. Tulgan, Managing Generation X: How to Bring Out the Best in Young Talent, W.W. Norton and Company, (New York, N.Y, 2000); R. Zemke, C. Raines, and B. Filipczak, Generation Gaps in the Classroom Generations at Work: Managing the Clash of Veterans, Boomers, Xers and Nexters in Your Workplace, AMACOM Books, (New York, N.Y., 2000).

29. Al Boyer and Cole Liveieratos, “Changing Character of Followers: Generational Dynamics”, Modern War Institute, June 16, 2022, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/the-changing-character-of-followers-generational-dynamics-technology-and-the-future-of-army-leadership/.

30. J. Jenkins, “Leading the Four Generations at Work”, American Management Association, January 24, 2019, https://www.amanet.org/articles/leading-the-four-generations-at-work/; U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, The Millennial Generation Research Review, U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation (2012), Accessed on November 30, 2022, https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/reports/millennial-generation-research-review.

31. Al Boyer and Cole Liveieratos, “Changing Character of Followers: Generational Dynamics”, Modern War Institute, June 16, 2022, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/the-changing-character-of-followers-generational-dynamics-technology-and-the-future-of-army-leadership/.

32. J. Notter and M. Grant, When Millennials Take Over, Idea Publishing, (Oakton, Virginia, 2015); Darlene Stafford and Henry Griffis, A Review of Millennial Generation Characteristics and Military Workforce Implications, Center for Naval Analysis, (Alexandria, VA, 2008), Accessed on November 30, 2022, https://www.cna.org/archive/CNA_Files/pdf/d0018211.a1.pdf

Download the PDF version: Click Here

Download the PDF version: Click Here